Testing is part of learning

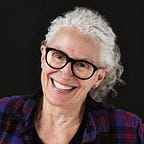

I can’t help it. I’m a developmental psychologist. When my grandchildren were infants I was fascinated with watching them learn to master their environment — including their parents. In the video above, my granddaughter Erwin was about 8 months old.

During the week prior to the making of this video, Erwin had figured out that she could directly manipulate social interactions. As shown in the video, she started reaching toward her Mom and Dad to indicate her intention to be picked up. Notice how emphatic her arm extension is, and how she makes eye contact as she reaches out. This isn’t instinctive behavior. Erwin is conscious of what she is doing. And she’s not just reaching out to be picked up. She’s begun pointing to objects to indicate interest or draw them to the attention of others. And she’s imitating actions like waving, clapping, and head shaking. Earlier on the day the video was made, when we were Skyping, she clapped her hands to get me to play pat-a-cake, and shook her head in order to get me to do the same — which she found hilarious. To her Mom’s dismay, Erwin was so excited by this new way of influencing her environment that she had stopped napping.

A few weeks before this video was made, most of Erwin’s actions were aimed toward physical mastery — learning to obtain objects and manipulate them in a variety of ways, learning to move herself toward things she wanted to manipulate, or playing with sound just to hear the results.

When she was learning to do these things, the physical environment provided most of the feedback. Although her parents were there to give encouragement, we all had the sense that it was the physical feedback that she craved — getting an object to her mouth, inching toward a favorite toy, pulling herself to stand.

Now she craves feedback from her parents; she has shifted her focus from physical mastery to social mastery. She reaches for Mom and gets picked up. She shakes her head and Mom shakes her head back. She points to a banana, and Dad brings it to her. She claps her hands, and Grandma plays pat-a-cake. And every time she undertakes a new action, she is conducting a test.

Testing really is part of learning.

Each time any infant tries out a new skill, she is conducting a test. Each attempt is part of an action-feedback loop. Repeated attempts to master a new skill form a series of these action-feedback loops. Each iteration is an exemplary test — in the sense that it is educative — that guides the infant incrementally toward a new level of mastery.

Interestingly, infants never tire of this kind of testing, even when the feedback is not instantly gratifying. In fact, much of the feedback is along the lines of, “almost, but not quite,” or “that didn’t work,” neither of which seem to get in the way of infant learning. For example, when Erwin first started reaching toward her parents to ask to be picked up, her action was not easy to read. It rarely got the desired response. She gradually learned that the reaching needed to be clearly directed toward the parent and accompanied by eye contact. Within a day or two of filming the video, Erwin was taking the skill for granted, and had shifted her attention to things she had not yet mastered, like figuring out how to get adults to do other interesting or gratifying things.

The natural action-feedback mechanism of infancy works perfectly, because the proverbial carrot is usually, due to the very nature of normal human environments, dangled at just the right distance. Good parents respond to early attempts at communication, rewarding them with interesting responses. However, success isn’t the only reward, because each success introduces a new “carrot” — another interesting possibility just beyond the infant’s reach. In this way, the action-feedback mechanism functions both as an aid to learning and as a motivator.

Aspects of this “carrot-and-stick” perspective on learning have been expanded and described in a variety of research traditions — e.g., as part of the notion of reinforcement feedback in social learning theory (Bandura, 1977), as zone of proximal development in Vygotsky’s (1986) work, as part of a complex process of assimilation and accommodation in Piaget’s (1985) work, and now in research on the dopamine opioid cycle. It is important, because it speaks both to how we learn and to our motivation for learning.

Good feedback plays two essential roles. First, it helps the learner decide what to try next. Second, it motivates the learner to keep striving toward mastery. And, as the infant example suggests, feedback cannot be reduced to simple reward or punishment. Ideally, it’s information that supports learning by being useful to the learner. Learners are not motivated by reward or punishment per se, but by an optimal combination of “not there yet” “almost” and “you’ve got it! But look — here’s another carrot!”